All-male groups of Bottlenose dolphins in human care

Abstract

The current trend in zoos is to house bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in harem groups, composed of one breeding male, a group of adult females, and their offspring. However, the separate lives of males, and the stable bonding between males are not illustrated. Since there is an approximately equal number of male and female offspring, housing dolphins in harem units inevitably leads to a large number of "surplus" males that need to be housed without access to females. Creating "bachelor" groups to take care of the male surplus problems in zoos has yet been more of a trial and error process than the result of a pre-planned strategy. As a starting point, the dominance relationships and the social interactions, possible problems with aggression within existing bachelor groups of Bottlenose dolphin and how to control this aggression will be studied. An important question to investigate is if male Bottlenose dolphins in human care form the same kind of alliances as seen in wild dolphins. The aim of the study is to identify the pros and cons of keeping Bottlenose dolphin males in bachelor groups in human care, and to produce some recommendations on how to set up and maintain such groups.

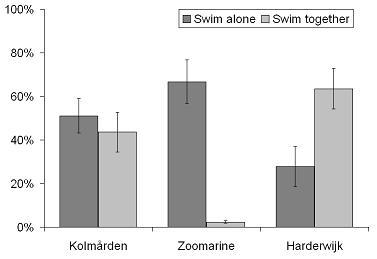

Observations were undertaken at three dolphinariums, one housing a traditional female group (Kolmården, Sweden) and two housing bachelor groups (Zoomarine, Portugal and Harderwijk, Holland) of Bottlenose dolphins. Data was collected on the amount of time selected focal animals spent swimming together versus alone. Also the frequency of aggressive behaviours such as jaw-clap, belly up and biting was observed. As a compliment, examining tooth-rake marks was used to indirectly measure missed aggressive behaviour.

There was a significant difference in the time the focal animals in the three facilities spent swimming alone and together. Dolphins at Zoomarine spent the least amount of time swimming together, on the average 2,4%. These dolphins swam significantly more alone than together. At Harderwijk, the dolphins swam significantly more together than alone. There was also a clear difference in time spent resting between the facilities. There was no resting at all in the Harderwijk males and at Kolmården one female rested for 1,5% of her time. As a contrast, the males at Zoomarine had an average of resting 28,2% of the time, either alone or together with another male.

The results obtained at Kolmården were consistent with previous studies, both at this facility and with other studies on groups of female Bottlenose dolphins. The social situation was very different between Zoomarine and Harderwijk. At Zoomarine, the males were separated almost all the time, which inevitably affected the association levels between them. A few days prior to the onset of the study at Harderwijk, a subadult male was introduced to the adult male group. This introduction was the most likely reason for the higher frequency of aggressive behaviour in this facility, since all these events involved the new subadult male.

These results indicate the importance of how bachelor Bottlenose dolphins groups are kept and what methods are used to managing their social interactions. Despite the fact the single males are kept in harem groups, this is not necessarily the best or even an acceptable social life for them. Free-ranging male dolphins are known to be very social and create strong bonds with one or two other males. This was also observed at Harderwijk. Hence, males should preferably be given the opportunity to form such strong bonds in bachelor groups. Then, instead of moving single males to female breeding groups, such male pairs could be chosen. This most likely would offer them a richer social life. However, it must be born in mind that these conclusions are based on a small sample size and should be treated with caution until the further studies are conducted.

Responsible for this page:

Director of undergraduate studies Biology

Last updated: