Results - Initial learning and intramodal stimulus transfer tasks

Pre-training

During the pre-training period (two weeks) the animals successfully learned to voluntarily approach the experimental set up and had made the association between bridge signal and food-reward. They had also learned to sample the two odor ports and search for the odor being presented through one of them. Upon identifying the odor and receiving a bridge signal, all elephants also reliably collected the food-reward through the grid above the odor port where the odor was presented.

Initial learning and odor discrimination: Experiments 1 and 2

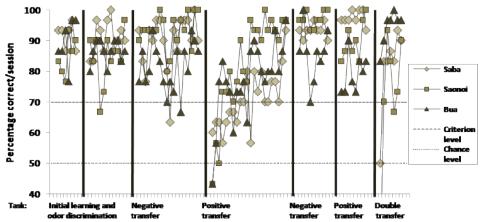

The graph shows the performance of the elephants during the initial learning and odor discrimination tasks. All three individuals reached the learning criterion within two sessions (p < 0.01) for both tasks, which corresponds to 60 trials and 120 stimulus contacts. A comparison of performance of the elephants in the present study to that of other species trained in similar two-choice odor discrimination tasks shows that the elephants performed at least equally good or better than other species tested before, including non-human primates. The speed of initial task acquisition of the elephants in the present study (120 stimulus contacts until reaching the criterion) is comparable to that of dogs (Lubow et al., 1973), rats (Slotnik et al., 1991) and mice (Bodyak and Slotnick, 1999), which all have been shown to need less than 150 stimulus contacts to acquire an olfactory discrimination task.

Asian elephants have previously been trained successfully in two-choice visual (Rensch, 1957; Savage et al., 1994; Nissani et al., 2005), auditory (Rensch, 1957; Heffner and Heffner, 1982), and tactile (Dehnhardt et al., 1997) discrimination tasks and they can readily learn such tasks. However, the number of stimulus contacts needed until reaching criterion in these other discrimination tasks clearly exceeds the quantity of stimulus contacts required by the elephants in the present study before mastering the task. These results suggest that elephants use olfactory cues more readily than for example visual or auditory cues to solve a learning problem. The performance of the elephants in the initial task acquisition shows that the learning speed of elephants is excellent and that they readily use olfactory cues when solving a learning task.

Intramodal stimulus transfer tasks: Experiments 3-7

The negative stimulus transfer tasks (in which the unrewarded odor was replaced by a new S-) presented no problems for the elephants and they all immediately performed above 70 % correct in the first session of each transfer. The change of the unrewarded odor had little or no effect on their high level of performance and these results are similar to those obtained for two species of primates (Hübener and Laska, 1998; Laska et al., 2003). However, for both squirrel monkeys (Laska and Hudson, 1993) and South African fur seals (Laska et al., 2008), a similar change of the S- initially led to a decrease in performance level. This effect was not seen in the elephants in the present study. The elephants readily mastered the two negative stimulus transfer tasks within two sessions (p < 0.01), that is, the minimum number of sessions needed to reach criterion.

The first positive transfer task (in which the rewarded odor was replaced by a new S+), however, proved to be more of a challenge and while Saonoi and Bua needed five and four sessions, respectively, Saba completed ten sessions before reaching the learning criterion (p < 0.01). Thus, the elephants needed between 240-600 stimulus contacts before mastering a first change of the rewarded odor. The performance of the elephants was comparable to the results obtained for the pigtailed macaques (Hübener and Laska, 1998), but inferior to that of the South African fur seals and spider monkeys (Laska et al., 2008; Laska et al., 2003).

This rather high number of stimulus contacts needed until understanding the task, might partially be explained by the rigidity of the elephant’s learned behavior (Nissani, 2008) and the strict training method by which elephants are usually trained and kept (Nissani, 2006). When training elephants in a free-contact system, establishing the trainer as being dominant is essential for human safety and therefore the animals are taught to listen to commands and perform certain behavior sequences (Whittaker and Laule, 2008). Taking own initiatives or breaking these sequences are usually punished which might affect the way that animals approach a problem even in other situations (Nissani, 2006). In the present study, the animals had to explore, take initiative and make their own decisions without being commanded to do so. Such a change in training method might at first have been confusing to the animals, especially when the exchange of the rewarded odor required the animals to decide for a new odor and change their response.

However, in the second positive transfer task, all individuals needed fewer stimulus contacts before reaching the learning criterion (i.e. two sessions) than during the first positive transfer. The decrease in the number of sessions and stimulus contacts needed before reaching criterion over time, suggests that the elephants showed a gradual learning of the task. Comparable results of understanding the concept and needing fewer trials over time for mastering a task have previously been found when training elephants in two-choice visual object discrimination tasks (Rensch, 1957; Savage et al., 1994). This gradual learning of the task has not been reported for other species tested in similar tests before, suggesting that this specific feature might be exclusive for elephants.

Finally, in the double stimulus transfer task both Saba and Saonoi reached the learning criterion within three sessions while Bua already mastered the task within two sessions (p < 0.01) .

Responsible for this page:

Director of undergraduate studies Biology

Last updated:

05/20/11