Results & Discussion

In 2015 a total of 620 trees were surveyed, with 973 finds of 24 red-listed epiphytic lichen species. The number of observations for each species varied between one and 432. The majority of the species (89%) analysed showed a mean decrease in both the reference and restoration plots.

Effects of conservation thinning on red-listed epiphytic lichens

General lichen abundance

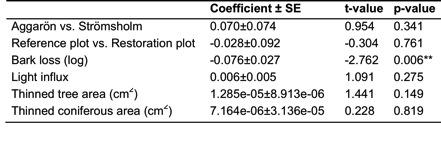

Bark loss had a negative effect on lichen abundance (Table 1), which is obvious since lichen disappear when bark is lost. Other than bark loss there are in general no clear indications of what might account for the general difference in abundance of red-listed epiphytic lichens on broad-leaved trees as a group.

The results of this experimental study point to that red-listed epiphytic lichens as a group in this case are not benefited by conservation thinning. This might be explained by the large difference in habitat preferences among the species studied. The conclusion of this result is that conservation thinning can be used in areas with red-listed epiphytic lichens without risking them. Of course consideration needs to be taken to the species composition at each site.

Species-wise

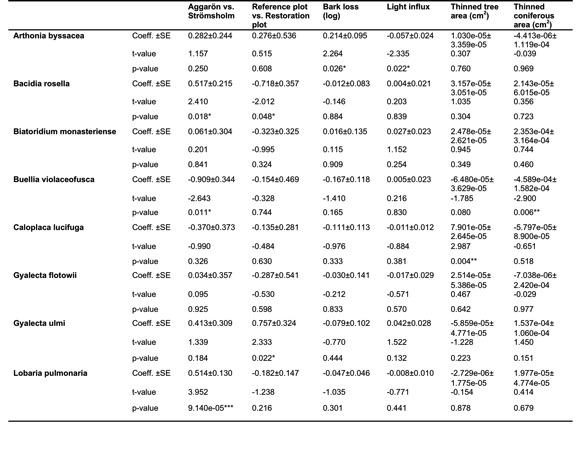

However, when assessing the effect of conservation thinning species-wise, two species were found to be affected. Only G. ulmi has been shown to actually benefit from restoration (Table 2). This is as expected as G. ulmi is a species that thrives in semi-open habitats like wooded meadows and pastures. B. rosella on the other hand, reacted negatively towards conservation thinning (Table 2). As B. rosella is found in both forests and more open areas it is reasonable to assume that the species might be resilient and therefor indifferent to the change.

If the aim of the conservation thinning is to benefit a specific species of lichen, conservation thinning might be a solution.

Dutch elm disease and Ash dieback disease

Effects of conservation thinning on Dutch elm disease and Ash dieback disease

The results showed a difference in the frequency of elms in each health-class between the two locations Aggarön and Strömsholm with a p-value of 4,799e-05. The elms of Aggarön seem to be slightly healthier as 27% were classified as either healthy or <50% affected, comparing to 3% at Strömsholm. It is interesting that the elms of Aggarön are healthier than at Strömsholm. This might be explained by the fact that Aggarön is a more isolated location, as it is an island. However, there was no difference in the frequency of ashes in each health-class between the two locations.

Furthermore, the results showed that there was no difference in the frequency of infected ashes and elms i n each health-class, between the reference and restoration plots, i.e. conservation thinning did not affect the frequency of infected elms and ashes. To conclude, it might not be needed to take consideration to Dutch elm disease and ash dieback disease when conducting conservation thinning.

Refugium for lichen species abundant on elm and ash?

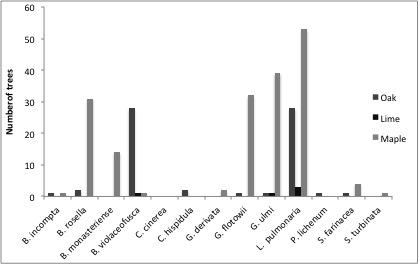

The species of red-listed epiphytic lichens that were abundant on elm and ash, i.e. the species that Dutch elm disease and ash dieback disease poses a threat to, were most common on maple and oak (Fig. 1). Especially maple has been found to be a good substitute tree by previous studies.

Responsible for this page:

Director of undergraduate studies Biology

Last updated:

06/15/16