Results

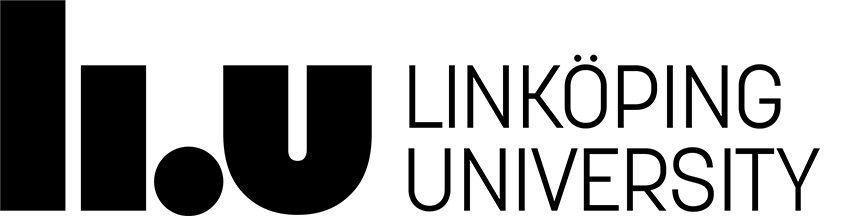

Dogs that vocalized during free talk spent a significantly higher proportion of time moving their tails (U = 210.0, p = 0,002; Figure 2) and jumping (U = 185.5, p = 0,040; Figure 2) than dogs that did not vocalize.

Differences in behaviour between refusal phase and affirmative phase

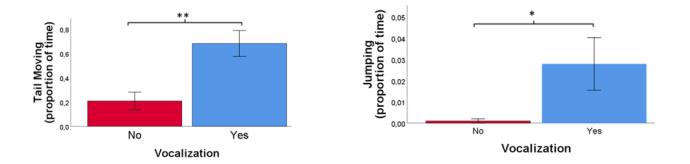

Dogs vocalized more often during the refusal phase than the affirmative phase with both teasers (Treat: z = 64.0, p = 0.042; Toy: z = 127.0, p = 0.071; Figure 3). Similarly, dogs whined significantly more often during the refusal phase with a treat as teaser than the affirmative phase (z = 114.0, p = 0.017; Figure 3).

Dogs also performed significantly more stress-related behaviours per minute during the refusal phase than the affirmative phase with a treat as teaser (z = 10.0, p < 0.001; Figure 3).

The owners had higher vocal intensity during the affirmative phase than the refusal phase (z = 183.0, p = 0.004), but the vocal frequency did not differ significantly between the refusal phase and the affirmative phase. Dogs had the same vocal intensity and frequency during both the refusal phase and the affirmative phase.

Turn-taking

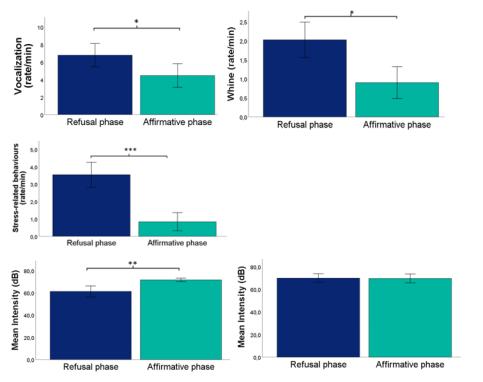

The mean proportion of overlaps for all analyzed dogs combined ranged from 14 - 50 % (table 2). The mean size of gaps during turn changes for all analysed dogs combined ranged from 0.8 – 1.4 s. The percentage of gaps that were smaller than one second for all analysed dogs combined ranged from 53 – 85 %.

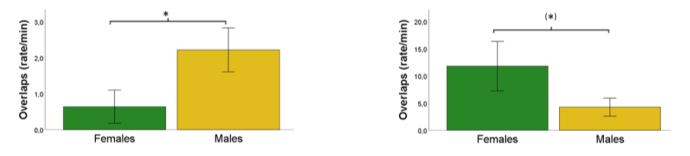

Differences between male and female dogs’ communication with their owner

During free talk females tended to perform more overlaps in proportion to the number of vocalizations compared to males (U = 8.5, p = 0.073; Figure 4). However, during the refusal phase in sessions with a toy as teaser, males performed significantly more overlaps per minute than females (U = 53.0, p = 0.048; Figure 4).

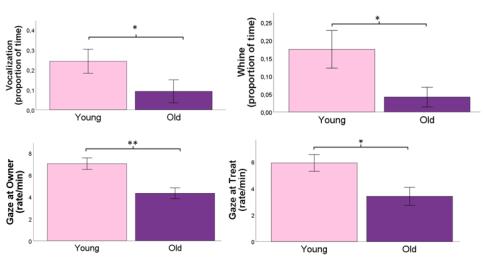

Differences between young and old dogs’ communication with their owner

Young dogs vocalized significantly more during the refusal phases (U = 26.5, p = 0.030; Figure 5) and also whined significantly more during these phases (U = 43.5, p = 0.034; Figure 5).

Young dogs gazed at their owner significantly more often than old dogs during the refusal phase with a treat as teaser (U = 25.0, p = 0.002; Figure 5). During this phase young dogs also gazed at the treat significantly more often than old dogs (U = 37.0, p = 0.014).

Responsible for this page:

Director of undergraduate studies Biology

Last updated:

05/22/19