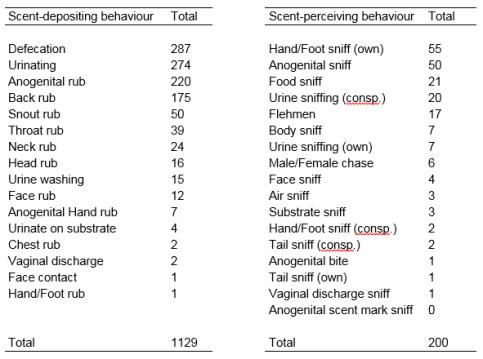

I collected a total of 1329 olfactory-relate behaviours.

Among all the 33 behaviours, 15 have never been previously described in any species of the genus Alouatta (anogenital-hand rub, head rub, neck rub, vaginal discharge, air sniffing, anogenital bite, body sniffing, face sniffing, sniffing of its own or conspecifics’ hand or foot, sniffing of its own tail or a conspecifics’ one, food sniff, sniffing at its own urine and vaginal discharge sniff).

The most frequently observed olfactory-related behaviours were defecation and urination, followed by anogenital rub. During the present study, I noticed that all howler monkeys urinate and defecate one after the other in the same place, or close to it, as the individual who preceded, and that those behaviours were performed mainly just before or during a period of troop moving. I suggest that the combined use of urine, faeces and anogenital rub in the context of locomotion, serve to mark a trail for other troop members to follow.

Males vs Females

Males performed significantly more olfactory related behaviours than females.

In particular, they performed more anogenital sniff, substrate sniff and urine sniffing of a conspecific that are behaviours reported to be used by other non-human primates to monitor te reproductive status of the females. So, it is possible that female howler monkeys use olfactory cues to communicate sexually relevant information.

Males performed also more face rub, throat rub, and urine-washing. Those are behaviours that have been observed in other species of howler monkeys as agonistic signals towards conspecific, especially in sexual context, to deter competitor and have access to the female.

Adult vs Young

Adult animals performed significantly more olfactory-related behaviours than young animals, probably because olfaction seems to be related to reproduction, and young animals are pre-puberty, that means that they are still sexually inactive. Furthermore, adults animals were the only performer of behaviours associated with copulation, such as flehmen and male/female chasing. These results enhance even further the role of olfactory communication in the context of reproduction.

One interesting finding was the one regarding the behaviour face sniffing that was performed only by the youngest member of the troop or towards its face. This behaviour seems to be involved in recognition of group members or social bonding.

Season and climate condition

From June to November the ambient temperature decreased, and I found that while the temperature was decreasing, the howler monkeys were performing more olfactory-related behaviours, and this may have happened due to the fact that with a lower (still above 20°C) temperature the monkeys are more active, the feed and move more.

During the rainy days, I observed a higher frequency of scent-depositing behaviours compared to non-rainy days. Just after the rain, the monkeys were performing a stereotypic sequence of behaviour that started with rubbing the back, the neck, and the head and ended with anogenital rub before either moving or changing position to rest. The literature lacks in regard to this event. However, in my personal opinion, three mutually non-exclusive reasons may explain those behaviours:

1. Renew scent-marks washed away;

2. Dry their fur;

3. Tingling or itching sensation.

Food choice

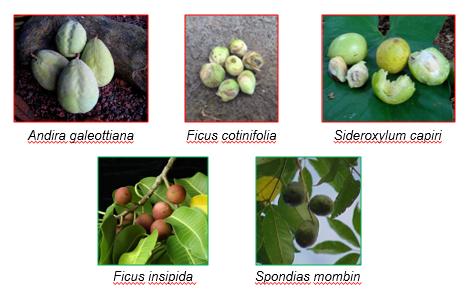

I recorded 21 instances of individuals sniffing at a fruit before eating it, while not a single instance of sniffing at leaves was observed. I also never observed the monkeys drinking water nor sniffing at the water.

I saw that howler monkeys on Agaltepec Island eat fruits from five different trees (Andira galeottiana, Ficus cotinifolia, Ficus insipida, Spondias mombin and Sideroxylum capiri), but only smelled at two of them: Ficus insipida and Spondias mombin. The major difference between the fruits from this last two trees and the other three was the colour: they were NOT bright green. It seems therefore plausible that howler monkeys use olfactory cues in fruit choice, when the visual cues alone are not sufficient to determine the ripeness of the fruits.

Responsible for this page:

Director of undergraduate studies Biology

Last updated:

05/30/17