Stress

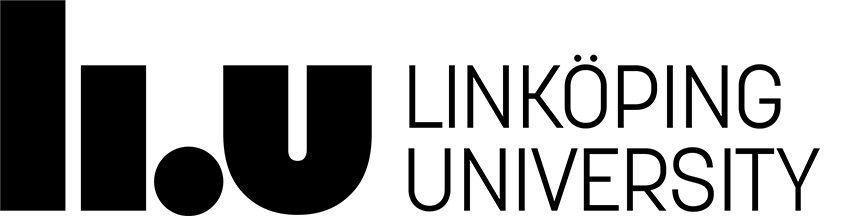

Stress is used as a primary measure of welfare in laying chickens however measuring welfare is a complex process due to variable commercial housing systems (Ralph et al., 2015; Graml et al., 2008). Stress is defined as ‘a state in which an animal is responding to a stressor’ (Fraisse and Cockrem, 2006). Stressors are literally defined as ‘anything that changes homeostasis’, or when an animal experiences a demand which exceeds the normal amount of resources available to cope with such demands (Morgon and Tronberg, 2007), whether the demand be physical or emotional (Fraisse and Cockrem, 2006). On a physiological level stress is defined as an activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA-axis) with an increase in the secretion of glucocorticoids such as cortisol and corticosterone (Cockrem, 2007; Jensen et al., 2014).

The primary glucocorticoid produced, as part of the HPA-axis, in chickens is corticosterone (CORT) which is released from the adrenal cortex (Cockrem, 2007; Ferrante et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2013). CORT levels are mediated through a negative feedback loop to the hypothalamus which prevent stress response overreactions and aid in protecting the animals from injury due to extreme fear responses (Wang et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). While the release of glucocorticoids is necessary for processes such as the fight or flight complex by increasing the blood glucose levels (Cockrem, 2007), prolonged exposure to high levels of glucocorticoids can have negative long term effects on the behaviour and physiology of animals (Ericsson et al., 2016; Jensen et al., 2014; Elfwing et al., 2015; Goerlich et al., 2012). Plasma corticosterone analysis is currently the most common method used to assess the welfare of commercial chickens; however other measures of stress may be required to fully understand the extent that commercial stressors affect commercial laying hens (Ralph et al., 2015).

Image from: https://i.pinimg.com/564x/23/9d/ed/239ded7a28d072a1f497b0d36ef5e800.jpg

Stressors experienced by commercial chickens

Commercial chickens are exposed to a multitude of stressors throughout their life such as; temperature stress, social stress, novel environments and transportation stress (Ericsson et al., 2016). Heat and cold stress can adversely affect the welfare and production of commercial laying hens (Scanes, 2016; Goerlich et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014; Matur et al., 2016). Cold stress has greater effects on commercial chickens than commercial mammals due to birds having a naturally higher body temperature, making them more sensitive to cold stress (Xie et al., 2017). Cold stress can cause a decrease in egg production; alter the efficacy of the nervous system, which ultimately reduces feed intake and growth rates. Heat stress has also been shown to have detrimental effects on commercial chickens (Mignon-Grasteau et al., 2015). Heat stress can decrease egg production, egg quality and compromise immune-efficiency leading to higher mortality levels amongst flocks of commercial laying hens (Mignon-Grasteau et al., 2015).

Commercial chickens usually experience social separation and regrouping several times between hatching to reaching adulthood (de Haas et al., 2012; Goerlich et al., 2012; Warnick et al., 2005; Jones, 1996). Regrouping chickens may lead to social instability, resulting in the chickens re-establishing the pecking order of the group due to new flock mates. More dominance-aggression is observed after regrouping, leading to an increase in overall flock stress levels (de Haas et al., 2012).

Image from: https://i0.wp.com/www.livestocking.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/panting-broiler-chicken-faced-with-heat-stress.jpg?w=645&ssl=1

One of the most common stressors experienced by commercial laying hens is exposure to novel environments and objects (Jones, 1996; de Marco et al., 2013). Chickens are frequently moved into novel environments, for example from a commercial hatchery to a rearing farm and then to an adult egg production farm, each move exposing the chickens to novel environments requiring habituation periods (Jones, 1996). Chickens are also exposed to novel objects, including feed and farm machinery, novel odours and novel noises, each of which can elicit stress responses (Jones, 1996; de Marco et al., 2013).

Another stressor which all commercial laying hens experience is transportation between facilities which can often be long distances (Matur et al., 2016; Goerlich et al., 2012; Jones, 1996; Compendio et al., 2016). Laying hens experience many transport events throughout their first year of life, from a hatchery to a rearing facility, to a laying hen facility, then finally to slaughter when their peak production period ends (Matur et al., 2016). Transportation itself creates a host of additional stressors to the chickens including; temperature variability, vibrations and loud noises (Matur et al., 2016).

Image from: http://www.panematrailers.co.uk/img/gallery/gall51_thm.jpg

The effect of early stress

Day old chickens, destined to become laying hens in commercial egg production systems are subjected to a host of different stressors from the moment they hatch; these include rough human handling, sex sorting, being in crates for long periods of time, and being transported long distances (Ericsson and Jensen, 2016; Ericsson et al., 2016). This early stress can have serious implications on chicken behaviour, physiology and immune-function (Gross and Siegel, 1980; Jensen, 2014), creating problems which later affect the production and welfare of laying hens (Archer and Mench, 2014). The early developmental period after hatching or birth, in which vertebrates are particularly susceptible to stress due to accelerated speed and increased complexity of brain development during this period (Ericsson et al., 2016). In chickens it has been found that stressful events experience early in life can influence the behavioural and physical responses until at least adulthood, whereas stress experienced later in life may only last a few days (Gross and Siegel, 1980).

Responsible for this page:

Director of undergraduate studies Biology

Last updated:

05/17/18