Background

Despite being fundamental to behavioural variation, the mechanisms driving cognitive differences both across and within species are still unclear. One of the most popular theories, the Social Intelligence Hypothesis, proposes that species living in more socially complex environments (i.e. larger group sizes) have to cope with greater social challenges (e.g. more individuals to recognize, social bonds to maintain and third-party relationships to track), than those living in less complex ones, or solitarily. As a result, it has been hypothesized that more socially complex species develop enhanced cognitive abilities. This framework was recently expanded to also include intraspecific variation, but whether this link occurs at this level is far from clear.

"The causality of the relationship between group size and cognitive performance remains unknown"

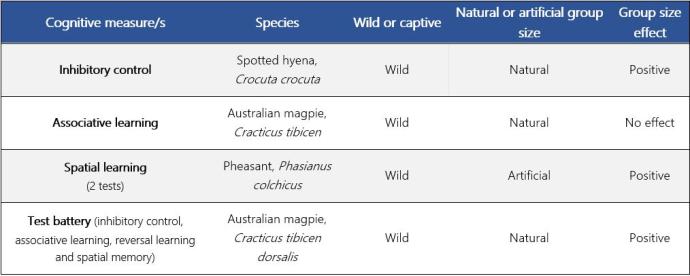

Unfortunately, less than a handful of intraspecific studies have so far assessed cognitive performance with ecologically valid group sizes. From the four published studies in only three different species, all, except one, report that individuals in larger groups performed better in a range of cognitive traits (Table 1). The cognitive traits in focus were inhibitory control, associative learning and/or spatial memory. These are well-defined cognitive traits, likely affecting individuals’ fitness. In addition, three out of the four intraspecific studies on the effect of ecologically valid group sizes on cognitive performance used unmanipulated variation in group size (Table 1). This makes unclear whether variation in group size drives variation in cognitive performance, or vice versa, which is crucial for our understanding of the causality of this relationship.

Table 1. Overview of all studies to date assessing the relationship between ecologically relevant group sizes and intraspecific cognitive performance in non-human animals.

Other factors may also differ between different group sizes and affect cognitive performance. Individuals in larger groups may experience more rest disturbances, lower predation risk and increased food competition than those in smaller groups. While more frequent rest disturbances can disrupt attention during tests and lead to worse cognitive performance, lower levels of predation may mean less need to be vigilant. This, in turn, could result in better cognitive performance. Increased competition may also enhance cognitive performance if individuals are stimulated to develop innovative strategies to access food, or if they become more food motivated (cognitive tests usually used food as rewards). At the same time, more competition may be detrimental if it prevents some individuals from having enough food for normal cognitive processing. Taken together, how group size influences cognitive performance within species may be more nuanced than predicted by the Social Intelligence Hypothesis. However, whether variation in group size affects cognitive performance through variation in social complexity, or through variation in other factors, has yet to be thoroughly investigated.

Responsible for this page:

Director of undergraduate studies Biology

Last updated:

05/18/20